Graham Greene: a literary life is a slim volume I found in The Book Grocer, a small chain of Melbourne Bookstores with an interesting if unpredictable range. It’s part of the series called ‘Literary Lives’. This is not a biography of Greene (see Norman Sherry’s monumental three volume work or Michael Sheldon’s one volume attack) but an extended essay by Neil Sinyard on reflections of Greene’s life in his work.

Looking for an author’s life in his or her work is a hazardous one. In Greene’s book of collected essays, he includes his assessment of Beatrix Potter, looking at the change in her style as she gets older and wiser. He includes the letter he received from her in response, which told him the books were published in a different order to the one in which they were written, so his conclusions were based on false assumption and in any case he should probably avoid this sort of Freudian analysis.

That said, I thought this book was a good overview of Greene’s work. It draws interesting conclusions from his early work as a reviewer and its effect on his writing. There is an interesting parallel between Greene and Hitchcock, both Catholic, working with political and personal intrigue, innocents falsely accused or out of their depths, and guilt. Hitchcock tried to buy the rights to Our Man in Havana, which would have been a better film if he had. But Greene refused to sell them to him and Sinyard, who writes on cinema and the relationship between film and literature, has a good theory why.

What I love about Graham Greene is what he called the splinter of ice in the writer’s heart: in moments of high emotion or vulnerability or confidentiality, there is that part sitting back and remembering it for use later in the work. I think all artists have to have that to some degree: Sondheim dedicated a song to a similar idea. Greene takes it as far as he can. I can feel his cold, unsentimental, almost pitiless eye in his work; even in what Greene would call his entertainments he sees past what fronts people may put on, to the fears and insecurities and deeply-felt beliefs that drive them. Greene, like Lear, sees the poor bare forked animal.

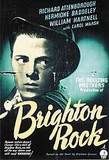

Greene hated being called a Catholic writer, preferring to think of himself as a writer who happened to be Catholic. He converted to marry his first wife, later lapsing (both as a Catholic and as a husband) but towards the end of his life started receiving the sacraments again. Four of his best novels, The Power and the glory, Brighton rock, The End of the affair and The Heart of the matter, all feature Catholics trying to balance the demands of their faith with the life that is before them. This to me is what faith and religion feels like – not the unthinking comfort that some would tell you, but a constant challenge. Engaging with God is not a cop-out but somewhere between an on-going duologue and endless wrestle.

Greene hated being called a Catholic writer, preferring to think of himself as a writer who happened to be Catholic. He converted to marry his first wife, later lapsing (both as a Catholic and as a husband) but towards the end of his life started receiving the sacraments again. Four of his best novels, The Power and the glory, Brighton rock, The End of the affair and The Heart of the matter, all feature Catholics trying to balance the demands of their faith with the life that is before them. This to me is what faith and religion feels like – not the unthinking comfort that some would tell you, but a constant challenge. Engaging with God is not a cop-out but somewhere between an on-going duologue and endless wrestle.

If you do want to read a biography of Greene, Sherry’s is authoritative but long, and Sheldon’s short but bitter and distorted. I’m not sure why people sit down to write biographies of people they don’t admire but there it is. There are other single volume biographies, with good reputations, as well as memoirs and Greene’s own autobiographical work but I have not read them, so cannot comment.

Greene is one of the great novelists of the twentieth century though he never won the Nobel Prize. Perhaps, as has been suggested, his apparent use of the suicide of the husband of one of his lovers, both of them Swedes, in one of his plays (there’s that splinter of ice again) alienated the Swedish judges. Perhaps his conventional style looked old hat in the era of modernism and postmodernism and his popularity suspicious. In any case, as Sinyard points out, he shares that odd distinction with giants such as Tolstoy, Ibsen, Conrad, Woolf , and Chekhov. (Hitchcock never won an Oscar for directing either.) Another writer Bryan Forbes challenges anyone to quickly name the last three recipients of the prize. Glittering prizes are one thing, great art is another. Greene is by turns empathetic, cruel, humorous and terrifying. But always, always, readable.

Greene is one of the great novelists of the twentieth century though he never won the Nobel Prize. Perhaps, as has been suggested, his apparent use of the suicide of the husband of one of his lovers, both of them Swedes, in one of his plays (there’s that splinter of ice again) alienated the Swedish judges. Perhaps his conventional style looked old hat in the era of modernism and postmodernism and his popularity suspicious. In any case, as Sinyard points out, he shares that odd distinction with giants such as Tolstoy, Ibsen, Conrad, Woolf , and Chekhov. (Hitchcock never won an Oscar for directing either.) Another writer Bryan Forbes challenges anyone to quickly name the last three recipients of the prize. Glittering prizes are one thing, great art is another. Greene is by turns empathetic, cruel, humorous and terrifying. But always, always, readable.