Lincoln and Kennedy are the bookends of presidential assassinations. There were attempts before and attempts since, as well as two other successful kills, but they are, so far, the alpha and omega of that story. Which is partly why their deaths attract the most attention. A quick google search for books on both topics will bring pages and pages of results, let alone web pages, papers, articles popular and academic, films, TV and yes, at least one musical, Sondheim's Assassins, which starts with Lincoln and ends with JFK. We probably don't need anymore - but here goes.

Lincoln and Kennedy are the bookends of presidential assassinations. There were attempts before and attempts since, as well as two other successful kills, but they are, so far, the alpha and omega of that story. Which is partly why their deaths attract the most attention. A quick google search for books on both topics will bring pages and pages of results, let alone web pages, papers, articles popular and academic, films, TV and yes, at least one musical, Sondheim's Assassins, which starts with Lincoln and ends with JFK. We probably don't need anymore - but here goes.

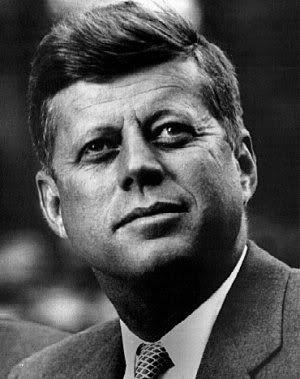

The Kennedy assassination is well-known, on film, and still controversial. How could a single gun-nut shoot down the president? Why was he killed himself while surrounded by policemen days later? Surely there is more to this than meets the eye. Coincidences, conflicting eye-witness reports, and inconsistencies all tend to prove there was a lie being told to the people.

Vincent Bugliosi would disagree. Bugliosi was a successful and experienced District Attorney in Los Angeles, prosecutor of the Manson Family, and the author of Helter Skelter. Having acted as prosecutor in a mock trial of Oswald, his professional curiosity was piqued, and the result is Reclaiming History: The assassination of President John F. Kennedy, a large (1600 pages) ambitious book that aims to put to rest the idea that anyone but Oswald was responsible for Kennedy's death. (I didn't actually read this book, but instead listened to Edward Hermann reading it. Which was good, but I didn't get any illustrations - of which there are 32 pages!) As for the inconsistencies, the coincidences, Bugliosi will tell you that is part of any real-life murder, which rarely have a scriptwriter to neaten things up.

It would be pointless for me to reproduce Bugliosi's arguments, and more importantly evidence, as it would be tantamount to reproducing the book. The first section, available as a separate book, Four Days in November (which was made into a film, Parkland) details the assassination and what immediately followed, hour by hour, minute by minute, and during the assassination itself, second by second. It is as thorough a retelling of the events from Kennedy awaking on November 22 to Oswald's burial on November 25 as you could ever find.

The second section goes through the main conspiracy theories and exposes their utter lack of evidence and their fantasist origins. Again, going into detail would be tedious, but in printed form Bulgiosi provided references and notes for you to follow. As an example, take the fourth shot. Oswald, as has been demonstrated several times, had plenty of time and expertise to make his three shots. But when the House Selected Committee on Assassinations in 1976 , lead by a Senator who believed in the conspiracy theory, handed down their report, they said there was a fourth shot, hence a second gunman and a conspiracy. They could not name anyone who was part of that conspiracy and in fact explicitly ruled out the usual suspects - CIA, the mob, FBI etc. Their only evidence of a second shooter was an audio tape of a motorbike that was supposed to be part of the motorcade, allegedly recording a fourth shot. It was the only evidence for a fourth shot, and the expert who identified it as such said the tape could only be supportive evidence and not evidence in itself. Apart from technical problems with this tape, we are supposed to believe that a motorcycle policeman close enough to hear four shots, 150 meters behind the car, neither revved his engine to join the rush to the hospital, nor turned on his siren, but instead continued in the same fashion as he did before. Moreover, other acoustical evidence on the tape suggests the 'fourth shot' took place a minute after the first three. Far more likely then, it was a motorcycle in another part of town and the shot, static or some other innocent noise.

The second section goes through the main conspiracy theories and exposes their utter lack of evidence and their fantasist origins. Again, going into detail would be tedious, but in printed form Bulgiosi provided references and notes for you to follow. As an example, take the fourth shot. Oswald, as has been demonstrated several times, had plenty of time and expertise to make his three shots. But when the House Selected Committee on Assassinations in 1976 , lead by a Senator who believed in the conspiracy theory, handed down their report, they said there was a fourth shot, hence a second gunman and a conspiracy. They could not name anyone who was part of that conspiracy and in fact explicitly ruled out the usual suspects - CIA, the mob, FBI etc. Their only evidence of a second shooter was an audio tape of a motorbike that was supposed to be part of the motorcade, allegedly recording a fourth shot. It was the only evidence for a fourth shot, and the expert who identified it as such said the tape could only be supportive evidence and not evidence in itself. Apart from technical problems with this tape, we are supposed to believe that a motorcycle policeman close enough to hear four shots, 150 meters behind the car, neither revved his engine to join the rush to the hospital, nor turned on his siren, but instead continued in the same fashion as he did before. Moreover, other acoustical evidence on the tape suggests the 'fourth shot' took place a minute after the first three. Far more likely then, it was a motorcycle in another part of town and the shot, static or some other innocent noise.

Not that evidence or lack thereof will put a conspiracist off their pet theory. Indeed, they will say people like myself are falling for the Big Lie, one told often enough so that people will believe it. But consider this: most people believe there was a conspiracy to kill Kennedy despite the utter lack of evidence. What then is the Big Lie and who is falling for it?

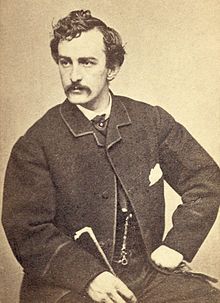

The image of John Wilkes Booth leaping from a theatre box to the stage, and breaking his leg in the process is imprinted on the historical imagination. It may also be wrong. Having shouted something - Sic semper tyranis? The South is avenged? A theatre full of witnesses disagree - he walked quickly from the stage through the wings to the stage door, mounted a difficult horse and rode off. The leg was broken, it seems, later on his ride. What else do we picture incorrectly?

Lincoln was only one of the victims on April 14 1865. His Secretary of State Francis Seward was also attacked that night, and left with horrific injuries, while the attacker assigned to Vice-President Andrew Johnson lost his nerve at the last minute. The conspiracy was ambitious in scope, months in planning, had different members coming and in and trying to get out, transformed from a single kidnapping to a planned triple-murder, and yet we only really know one name, that of Booth. And having read American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies by Michael W Kauffman, I'm not entirely sure Booth would be unhappy about that. What he would be deeply grieved by would be the high esteem Lincoln is held in today, and why: freeing the slaves, and prosecuting a successful war against the Confederacy.

Like Bugliosi's book, this is a detailed account of the assassination. As this was a long conspiracy which started before November 1864, naturally the author can't go into hour by hour build up, but for the assassination itself and its immediate aftermath, Kauffman does just that. By the time the other conspirators were tried and hanged it was July 1865 so this book is covering a lot more time in a much more user-friendly length. It is a very readable book, wearing its deep research lightly. Clearly the emphasis is on Booth, his colourful family, his life and motivations. Again there are myths and misconceptions here that Kauffman is keen to clear up. Booth's career was not on the wane, nor was he losing his voice. His plan to kidnap Lincoln and take him to Richmond was a wild one, but not without possibility while the war was continuing. But he dithered so long, Robert E Lee surrendered and people were waiting for the other Southern armies to follow suit. Those who had heard of his plan mocked Booth and his grandiose scheme. The South was falling, Booth was losing face, so out of vanity and bitterness, he crept into the theatre box and shot the President at point blank range.

Like Bugliosi's book, this is a detailed account of the assassination. As this was a long conspiracy which started before November 1864, naturally the author can't go into hour by hour build up, but for the assassination itself and its immediate aftermath, Kauffman does just that. By the time the other conspirators were tried and hanged it was July 1865 so this book is covering a lot more time in a much more user-friendly length. It is a very readable book, wearing its deep research lightly. Clearly the emphasis is on Booth, his colourful family, his life and motivations. Again there are myths and misconceptions here that Kauffman is keen to clear up. Booth's career was not on the wane, nor was he losing his voice. His plan to kidnap Lincoln and take him to Richmond was a wild one, but not without possibility while the war was continuing. But he dithered so long, Robert E Lee surrendered and people were waiting for the other Southern armies to follow suit. Those who had heard of his plan mocked Booth and his grandiose scheme. The South was falling, Booth was losing face, so out of vanity and bitterness, he crept into the theatre box and shot the President at point blank range.

His other stated motivation was Lincoln's supposed tyranny. And he was not alone in that thought. Suspending habeas corpus and other sections of the Constitution for the duration had made Lincoln some bitter enemies, and more than one of them had wondered out loud and on the record where was the Brutus to stop this Caesar. Booth was consciously following in the Roman's footsteps to save a Republic. But even then he waited too long, by a day. As Kauffman so elegantly puts, it, "Booth had hoped to to kill Lincoln on the Ides and highlight his resemblance to Caesar; but instead he shot him on Good Friday, and the world compared him to Christ."

But Booth's victims went far beyond the President. Any hope of mercy for the defeated Confederacy was gone. Lincoln's wife was eventually committed. Henry Rathbone who was seriously injured trying to capture Booth in the theatre box, went mad with guilt years later, murdered his wife and saw out his days in an asylum. Seward never fully recovered from his wounds. Booth would write to people with veiled hints, including Vice President Johnson, so as to implicate them in the conspiracy if it went wrong, to the point where lives and careers were damaged and destroyed, and people still ponder if Johnson was part of it. Booth was a vain, calculating and cunning man, who was a successful actor, and a successful assassin, whose actions brought more pain and trouble for the Southern states he was claiming to protect. Sic semper indeed.

Conflicting witness reports, inconsistencies, and coincidences are scattered throughout both the deaths of Lincoln and Kennedy. In one case we don't even consider them important, in the other we use them to create conspiracies to implicate the world. Lincoln died in a simpler time, we in the grip of the parochialism of the present would say, so his death was simpler. Kennedy was our hero, and heroes don't get killed by misfits. Extraordinary men get killed by extraordinary means, vast conspiracies, full of hundreds of evil men. But life is not neat nor well-written. A lone gun nut reaches for his moment, and the rest is history.