Being a spy is not easy, if you enjoy receiving credit. The better you are, the fewer people know about you. The best operations are the ones no-one ever discovers. (James Bond, by this standard, is one of the most hopeless spies ever. Everyone knows who he is.) Nor is much good for those who enjoy simplicity. You operate in a strange world of double-think and triple-think (“Now we know they know but they know we know they know but they don’t know that we know that they know we know they know, which gives us the advantage...") And you can never be honest, even with immediate family. The real world of spying seems to be a world of eccentrics and oddballs in a miasma of mistrust.

And the efficacy of espionage is one that is constantly under question. The better the information you gain, the more you tend to distrust it. Are the enemy playing with us the same way we play with them? Are they as good as us? Are they better? Despite all that, or perhaps because of it, I find true spy stories fascinating. In particular, stories from World War Two. These stories tend to have clear-cut goals and endings, which helps.

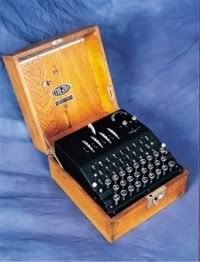

The greatest intelligence breakthrough of WWII was codenamed Ultra: the Allies broke the German code and were reading the bulk of all Axis communications. The Enigma machine was supposed to create unbreakable code, but thanks to the efforts and bravery of Polish soldiers, British sailors and the brains of an eclectic bunch of men and women at Bletchley Park, Axis secret communications had been compromised from the earliest days of the war. But this was kept secret for decades after the war had finished. (Incidentally, if you ever work out how the code-crackers did it, please let me know. I have read several accounts and still don’t understand.)

It is because of this official secrecy that old stories can be retold with more and better information. One of the greatest and most successful operations of WWII was Operation Mincemeat. A dead body with false plans for an invasion of Sardinia was floated ashore in Portugal, in hopes that the Germans would get a hold of them. All went to plan and many German troops, artillery and other materiel were transferred to Sardinia and were nowhere near the real attack on Sicily.

Once the war was over, rumours about this operation began to spread, despite it still being an official secret. As a result, Ewan Montague, the officer in charge of the operation, was given permission to publish an account of it, under the evocative title ‘The Man who Never Was’, which was a best seller then a successful movie. However, Montague was not able to tell the whole story. Much of their information on German activity was through the still-secret Ultra. Moreover, he felt a moral duty not to reveal the identity of the dead man who went to war as ‘Major Martin’.

Sixty years later and these restrictions no longer apply. Ben Macintyre, a British journalist, has written an exciting and fascinating account of the operation, under the simple title Operation Mincemeat. The bare bones provided by Montague are all present but now with more meat, complete with double-agents and cross-dressers. And the story of the man who became ‘Major Martin’ is pathetic and touching. It’s a great read and I recommend it, along with another of Macintyre’s book, Agent Zigzag.

Some of the men in Operation Mincemeat appear in this book too. Agent Zigzag was Eddie Chapman, a thief and safecracker in England before WWII, who started the war in a Jersey prison and ended it back among the demimonde of London’s Soho. In between those times, he volunteered to spy for the Germans on the English, then was enlisted by the English to spy on the Germans. He lived in France, England, Norway and travelled to Germany. He proposed killing Hitler at a Nazi Party Rally in Berlin but his offer was knocked back. He got engaged to two women, one of which had his daughter but he married a third woman. He betrayed his German masters but had his spymaster at his daughter’s wedding years after his story became known. He wasn’t a dull man.

Like Operation Mincemeat, Chapman’s story has been a book and a movie but much information was suppressed. Again, McIntyre fills in the gaps and provides colourful background, including a German spy who studied Morris Dancing, and a concentration camp inmate who ends up butling for Clark Gable after the war. And it is filled with incidents that beggars belief. For example, in London in 1944 and coming to the end of his espionage career, Chapman asked his colleagues to help him find the girl he left behind in 1939. They were in a crowded restaurant and Chapman looked around to find someone who looked like her as a reference point. ‘That girl looks like her from behind. Actually that is her.” Not even Dickens would write a scene like that. Well, maybe Dickens, but no-one else.

Like Operation Mincemeat, Chapman’s story has been a book and a movie but much information was suppressed. Again, McIntyre fills in the gaps and provides colourful background, including a German spy who studied Morris Dancing, and a concentration camp inmate who ends up butling for Clark Gable after the war. And it is filled with incidents that beggars belief. For example, in London in 1944 and coming to the end of his espionage career, Chapman asked his colleagues to help him find the girl he left behind in 1939. They were in a crowded restaurant and Chapman looked around to find someone who looked like her as a reference point. ‘That girl looks like her from behind. Actually that is her.” Not even Dickens would write a scene like that. Well, maybe Dickens, but no-one else.

And in the hall of mirrors that is espionage, nothing is ever certain. It is entirely possible that both Mincemeat and Zigzag were rumbled by German spies - spies who were quite happy to see Germany lose the war and so kept their suspicions to themselves. We will probably never know the entire truth.

World War Two continues to fascinate, as the flow of new books, games, movies and television attests. Despite the moral questions that have arisen, it is still clearly a war against an evil enemy, that we were right to fight and grateful to defeat. Mark Steyn in his column on ‘Saving Private Ryan’ rightly criticises the screenwriters for suggesting that defeating Hitler was not a sufficiently moral motivation for their characters. How moronic, how vacuous, how sadly desperate to show their liberal credentials, that the writers don’t like war. No-one likes war, soldiers least of all. Nor has anyone really written a pro-war book. Even the Illiad, which glories in descriptions of mythical battle, shows the gory reality of men thrust through with spears choking out their lifeblood in the dust, the poetry making the moment all the more visceral. And if we were all reasonable people, there would be no war. But we are not all reasonable people, and all of us are unreasonable at times. War shows humanity at its worst but also at its best. And for that reason, it will always fascinate.

No comments:

Post a Comment