Everyone likes a good murder. So much of our TV still depends on whodunit, and in shows like 'NCIS', 'CSI:Somewhere' and 'Law and Order: Cops and a Lawyer', the forensic evidence is always a key part of the case. This science has come a long way since police photographers took a shot of the eyeballs of one of Jack the Ripper’s victims, hoping an imprint of the killer would still be there. One of the key figures in this transformation was Sir Bernard Spilsbury.

Everyone likes a good murder. So much of our TV still depends on whodunit, and in shows like 'NCIS', 'CSI:Somewhere' and 'Law and Order: Cops and a Lawyer', the forensic evidence is always a key part of the case. This science has come a long way since police photographers took a shot of the eyeballs of one of Jack the Ripper’s victims, hoping an imprint of the killer would still be there. One of the key figures in this transformation was Sir Bernard Spilsbury.

Spilsbury was a pioneer of forensic medicine in the first half of the 20th Century. Indeed, he became a superstar, his appearances making headlines and his pronouncements accepted as fact. Two cases that made his name were the cases of Dr Frederick Crippen and George Joseph Smith, the Brides in the Bath murderer. Jane Robins’ new book, The Magnificent Spilsbury and the Case of the Brides in the Bath, examines Spilsbury’s early career, which covers both these cases and another, all of which depended on Spilsbury’s evidence to hang murderers.

George Joseph Smith it seems was charismatic and dominating. He would marry women after a whirlwind romance. Then, within weeks, he would then have them make wills with him as beneficiary, get any money from their family that they were entitled to, and murder them by drowning them in a bathtub. He did it three times (meanwhile conning other women out of their money) before he was caught. He used false names so it took a while before anyone noticed the similarities. Spilsbury’s evidence was crucial to the conviction.

Robins in actually far more interested in the women who were the brides than Spilsbury or Smith. She examines their lives, and more broadly the roles of women in Edwardian society, to find what led them to marry and be killed by George Smith. It’s an interesting and worthy idea and I wish she or her publisher had more courage to back this idea than pretend the main focus is Spilsbury. Why not “The Brides in the Baths”? It is always good to give the victims of famous murderers their due as human beings, and Robins does this well.

There are some odd aspects to the book. In examining the human remains in Crippen’s house, Spilsbury identified some skin as scar tissue, thus identifying the body with Crippen’s wife, while his colleague found traces the poison with which she was killed. In both cases they were looking for what they found. In other words, their findings could well have been coloured by their expectations. But Robins says this didn’t seem to bother anyone. Yet within two pages, she reports the defence barrister asking if they had been told what they were looking for. It seemed to bother him.

There are some odd aspects to the book. In examining the human remains in Crippen’s house, Spilsbury identified some skin as scar tissue, thus identifying the body with Crippen’s wife, while his colleague found traces the poison with which she was killed. In both cases they were looking for what they found. In other words, their findings could well have been coloured by their expectations. But Robins says this didn’t seem to bother anyone. Yet within two pages, she reports the defence barrister asking if they had been told what they were looking for. It seemed to bother him.

And in her conclusion to the Crippen trial, she reveals an alternate defence that was mooted at the time by another lawyer but never presented, which incorporated all the scientific evidence but put a different spin on circumstances and motivation. Then she says the lawyer was suggesting the scientific evidence could not be relied upon. But there is no such suggestion in the theory, quite the contrary. Why say this? I can only conclude that she was so keen to demonstrate that Spilsbury’s work was not as infallible as he, and the courts, liked to think, that she too was seeing what she wanted to see.

And it seems Spilsbury’s work was not as good as was thought. As he got older and more famous, the acclaim went to his head and he was not as careful as he should have been, and his pronouncements made with more certainty than was proper, and accepted by courts too readily. Late in his career, during World War Two, he was asked to assist with Operation Mincemeat, when a dead body was floated ashore in Spain with false plans for an invasion of Sicily. When a suitable body was found, they asked Spilsbury to examine it to see if it were possible to know that the man had not drowned. Spilsbury said there was nothing to worry about but he was wrong. The man had died by taking poison and there were burns in his mouth and throat and any worthwhile pathologist would have spotted this relatively easy. Wrong or arrogant? Did Spilsbury make a mistake, or just assume that a Spanish doctor would not have spotted it? Either way, this error, which was documented in an earlier book, does not make its way into Robins book, though she it suits her argument and she specifically mentions Operation Mincemeat. And to be fair, the ruse was not discovered; maybe Spilsbury was right all along. But Robins doesn’t give herself space to examine the later career of Spilsbury, when his flaws became more apparent. Instead she whips through the latter part of his career in a chapter, and her conclusion is weak from lack of detailed argument.

And it seems Spilsbury’s work was not as good as was thought. As he got older and more famous, the acclaim went to his head and he was not as careful as he should have been, and his pronouncements made with more certainty than was proper, and accepted by courts too readily. Late in his career, during World War Two, he was asked to assist with Operation Mincemeat, when a dead body was floated ashore in Spain with false plans for an invasion of Sicily. When a suitable body was found, they asked Spilsbury to examine it to see if it were possible to know that the man had not drowned. Spilsbury said there was nothing to worry about but he was wrong. The man had died by taking poison and there were burns in his mouth and throat and any worthwhile pathologist would have spotted this relatively easy. Wrong or arrogant? Did Spilsbury make a mistake, or just assume that a Spanish doctor would not have spotted it? Either way, this error, which was documented in an earlier book, does not make its way into Robins book, though she it suits her argument and she specifically mentions Operation Mincemeat. And to be fair, the ruse was not discovered; maybe Spilsbury was right all along. But Robins doesn’t give herself space to examine the later career of Spilsbury, when his flaws became more apparent. Instead she whips through the latter part of his career in a chapter, and her conclusion is weak from lack of detailed argument.

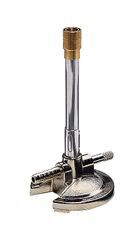

Spilsbury himself eventually realised his work was deteriorating, and the idea broke him. He gassed himself in his laboratory soon after the war.

This book is worth reading, particularly if you like a good true crime story. However, with a clearer focus and a more open approach, it could have been better.

No comments:

Post a Comment