Making up quotations

to suit yourself is not new. One

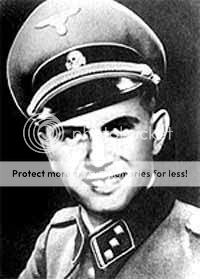

of the most popular fauxtations of WWI, the British army being lions led by

donkeys, was created by the man who “quoted” it, British historian Alan Clark.

He seems to have adapted it from other sources, about other wars about other

armies, to use in his book, The Donkeys,

about British military offencives during the war. As an image, it was picked up

by the creators of Oh what a lovely war, which depicted British generals as

incompetant at best, and callous butchers at worst. This image in popular

culture was still in use in Blackadder

goes forth, which had General Melchett as incompetant and callous, and had

Haig literally throw (model) soldiers into a bin while planning an attack.

But popular culture may

not be your best guide to history. A shock, I know. Douglas Haig’s reputation

went from respected

in the aftermath of the war, until his relatively early death in 1928, through to

villainy in the Sixties, as part of the antiwar movement of the time, to a more

balanced and nuanced rehabilitation more recently. No-one is claiming he never

set a foot wrong, or did not make decisions that cost thousands of men’s lives

needlessly, but his reputation as unimaginative, unfeeling, and incompetant is

nevertheless undeserved. Indeed one of his earliest critics, who criticised him

during the war, was Winston Churchill. Writing his history of World War One

afterwards, he was forced to admit, given the circumstances and resources

available to Haig, Churchill’s respect for him grew.

Water Reid’s Douglas Haig: Architect of victory is

part of the move to redress this imbalance. Reid does not argue Haig was the

best General available to the British, but he argues he was the best Commander

in Chief, a role that demands much in administration and organisation and human

resources, as well as military concerns. Haig oversaw an increase in his army

from three hundred thousand to three million men (including soldiers from the

Empire) and a revolution in military technology in the same time that has never

been equalled. Far from being unimaginative or staid in tactics, he increased

the engineering corps’ experimental section from by a factor of seventeen and

was enthusiastic to introduce new weapons such as tanks that would help his

soldiers. No other man at the time had this capability. By war’s end, the

British army was the most efficient army on earth, bringing together infantry,

armour, artillery and air support together, using tactics painfully learned,

and in an attack that drove the German army from the centre of France back to

the German border. Other experts, generals, politicians, expected the war would

last until 1919. Haig was the only one, literally, who saw how the war could

end in 1918, and was central to making it happen.

Churchil of course was

Prime Minister of Great Britain in WWII. By this stage he was a veteran of

three wars, including the First World War. He was a man of almost indominatable

courage, imagination and energy. It would not be an exaggeration I think to say

that Britain would have lost the Second World War without him. And if Britain

had lost, sought peace with the Nazi regime, how would the attack on Russia

have gone then, with a full German army concentrated on one side, and an

entirely

unsupported USSR on the other? For all of the astonishing tenacity and

courage of the Russian soldier, and their leaders’ disregard for their welfare,

the modern world would be very different.

Carol D’Este’s book Warlord: a life of Winston Churchill at war 1874 - 1945, is a study of Churchill as a warrior both on the field and as

a leader of a warring nation. As a

leader Churchill was responsible for some dreadful decisions that cost many men

their lives such as the attacks on Gallipoli, Norway, and Greece. Yet no-one

else could have done what he did, invigorated the British nation to stand and

fight when nearly all hope was gone, and their allies defeated. In his failures were elements of his

greatness – imagination, the search for a bold stroke, his unwilliness to do

nothing when danger was present. He was a flawed leader, and D’Este doesn’t

pretend otherwise but he was a great man, and in the right place at the right

time.

It is one of the

ironies of Churchill’s life that he was to oversee the transition from Empire

to a small nation on the second tier. By allying with the US and the USSR, he

ensured the defeat of Nazi Germany but he also brought in the next generation

of great powers. Churchill was central to the war effort up to 1941. Afterwards

he was not, and he knew it. He still made his presense felt, and had his

influence and of course his wonderful oratory, but Britain’s day as a world

power was waning, and all he could do was eulogise the sunset.

Churchill knew war

personally, had seen the massacre at Omdurman, (which De’Este sees as the

beginning of the war between the Muslim and the West still going on today) and fought

in the trenches in France. And yet he gloried in battle, and even in his

sixties, leading the nation, yearned to grapple with the enemy personally.

Robert E Lee said it, but Churchill knew what he meant: “It is well that war is

so terrible, else we shoud grow too fond of it.” This conundrum, love of battle

and awareness of it’s horrors also fed into Churchill’s leadership.

Churchill knew

something else. He may have forgotten it in the attack on Italy but he knew it.

Going to war means you have to know what you are fighting for, and you have to

go all in or not at all – “war to the knife”. As we grapple with the Middle

East, this is worth remembering for all our leaders.

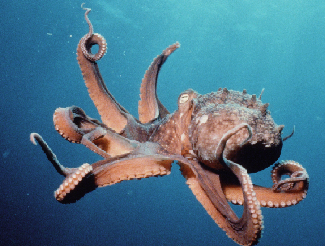

Oh enough war. I have

a book on octopuses now.