Sadly, ever since I graduated as a History teacher in 1990 from the University Queensland, all I have been allowed to teach is SOSE – Studies of Society and the Environment, an amalgam of History, Geography (which I have never studied), Law (same) Citizenship Education and anything else they can shoehorn in. I no longer teach, so maybe things have changed, or are changing. All I know is for students up to age fifteen, the Queensland Government, and they are not alone, don’t think History is worth its own subject.

The trouble with History is that it’s all over by the time we get there. And even if we’re there at the time, our stories could be contradictory if not downright irreconcilable. We cannot study history, we can only study what has been left behind – documents, photographs, physical evidence, personal accounts and other evidence. But history can encompass all other subjects. If you ignore history, you ignore everything that has happened up till now. That can’t be a good idea.

The nature of history study has given rise to many different theories of how and why we should study history. “So, can historians tell the truth about the past? Should history be written for the present, or for its own sake? Is it possible to see the past in its own terms? Should we make moral judgments about people and actions in the past? Are histories shaped by narrative conventions, so that their meaning derives from their form, rather than the past itself?” (p3) Ann Curthoys and John Docker, two Australian historians pose and examine these questions in their book, Is history fiction? , by showing what answers great historians through the ages have given. What follows is an examination of the study of history from the ancient Greeks through to present day, from the war between Persia and Greece, through to the history wars of the USA, Japan and Australia.

The nature of history study has given rise to many different theories of how and why we should study history. “So, can historians tell the truth about the past? Should history be written for the present, or for its own sake? Is it possible to see the past in its own terms? Should we make moral judgments about people and actions in the past? Are histories shaped by narrative conventions, so that their meaning derives from their form, rather than the past itself?” (p3) Ann Curthoys and John Docker, two Australian historians pose and examine these questions in their book, Is history fiction? , by showing what answers great historians through the ages have given. What follows is an examination of the study of history from the ancient Greeks through to present day, from the war between Persia and Greece, through to the history wars of the USA, Japan and Australia.

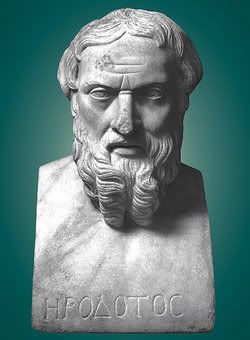

History, they suggest, tends to fall into two broad streams (with numerous tributaries, billabongs, creeks, puddles and how far can I extend this metaphor?) that derive from the two fathers of Western history (the masculine word is significant) Herodotus and Thucydides. Herodotus wrote The Histories, on the Greco-Persian Wars, and Thucydides The History of the Peloponnesian War, when Athens celebrated its victory over Persia by attacking Sparta and trying to create an empire of its own.

Both authors did extensive research, finding documents and other evidence and talking to eye-witnesses, and ordering their findings into narrative forms. But while Herodotus took a wide view, finding sources and material from many countries and classes in society, including non-Greeks, women and commoners, Thucydides focused on great and powerful leaders and took a much more linear approach, focusing on politics and military. Where Herodotus was prepared to say when he could not decide on the truth of a situation, Thucydides would give us his verdict.

The authors of this work follow these two approaches through to today, including the work of such names as Ranke, Macaulay, Beard and through to Simon Schama. When a book is a survey of a topic, it’s always a good sign if it makes you want to read further in the area. I have a copy of Herodotus gathering dust on my shelf but I am now taking it down. I have seen Schama on TV, but now I am determined to actually read his words. This is a fascinating book worth reading by anyone with an interest in history, expert or layperson like myself.

The answer to the question in the title is ‘yes and no’, which they give in the introduction. Why they think so makes up the book. Like most philosophical questions, there is no easy answer. Historians from Herodotus on have used literary methods to create their works, such as narrative and characterisation. The biggest difference between the historian, and the historical novelist, who sometimes claim to be doing the same work, is that the historian is bound to write with respect for and affected by the facts as they have found them. This novelist is not. It is a crucial difference. We should be able to trust the facts in a history, even if we disagree with the interpretation placed upon them. A novelist can make up anything he or she wants, if it makes the story or the characters more interesting, and they are right to do so.

Not that all historians are above ignoring or changing facts as they find them when they are inconvenient. But these are not good or trusted historians. This process is sometimes referred to as Pilgerisation, after John Pilger, the Australian journalist. Perhaps we should call it Moorism, after Michael Moore’s ‘documentary’ work. But Pilger and Moore, you may say, have their heart in the right place. I say a lie is a lie is a lie. But that’s a whole ‘nother argument, perhaps for another time. But if this approach is taken to extremes, we end up in David Irving territory. A terrific read on his trial is Telling lies about Hitler, The Holocaust, History and the David Irving trial, by Richard J Evans, one of the Defense’s expert witnesses. (It is always worth reminding people that it was Irving who brought the action.) Not only does it make clear Irving’s reprehensible actions, but is also a clear explanation of good historical practice. It was not Irving’s lack of formal qualifications that invalidated his work as an historian – anyone prepared to do the work can be an historian – but the way he deliberately falsified evidence, and that every time he did so it was to bolster his own beliefs that the Holocaust has been exaggerated and that Hitler was not responsible for it. You cannot make up the facts to suit yourself. Sadly, you can still read Irving’s figure for the number of dead killed at Dresden, which he exaggerated by a factor of ten, in other text books.

This book gave me clarity on some topics that have confused or daunted me. I’m still no expert on post-structuralism or post-modernism, but it turns out I’m not alone. Even critics and fans of Foucault, for example, seems to have a fuzzy idea on what Foucault was about. I still think getting hung up on theories is like examining the frame of the Mona Lisa – some interest sure, but hardly the point.

The chapter I found particularly illuminating was on Feminist historians. Herodotus wrote a lot on the role of women in his time, and their effect on the great events he was chronicling. As Thucydides’ style of history became more prevalent, the role of women became almost forgotten. Women found it difficult to get into the classes, let alone the profession, at universities. Male historians wrote for other male historians, and their subject was feminised as Clio, the Muse of history, or Historia. Ranke even compared a new archive he had discovered as ‘ absolutely a virgin’ and longed to ‘have access to her … whether she is pretty or not.” (p 99)

The chapter I found particularly illuminating was on Feminist historians. Herodotus wrote a lot on the role of women in his time, and their effect on the great events he was chronicling. As Thucydides’ style of history became more prevalent, the role of women became almost forgotten. Women found it difficult to get into the classes, let alone the profession, at universities. Male historians wrote for other male historians, and their subject was feminised as Clio, the Muse of history, or Historia. Ranke even compared a new archive he had discovered as ‘ absolutely a virgin’ and longed to ‘have access to her … whether she is pretty or not.” (p 99)

But being excluded from books and university departments does not mean excluded from history. What I found interesting about this chapter was the arguments within Feminist history eg does focusing on the assumed powerlessness of women also remove any responsibility they may have for the good and harm done in their time? Is this approach merely a different way of defining women through a masculine perspective? Is an indigenous female historian supposed to identify herself more by her sex than her race? The arguments still go on but, the authors end their chapter with a quote from Jill Matthews: “By good I mean …recognizing that sometimes gender does not matter …the fact of someone being a man or a woman may not be the most important thing about them or their behavior… using gender as a tool to analyse other more important historical categories rather than making it the central issue.” (p178) I think in the end, the bringing to light of the histories of forgotten people may or may not substantially change our picture of the past, but it does give it much more detail, clarity and meaning.

What is history? This is a question that involves all of us, every time we see an historical film, read an historical novel, read an article to purports to give us this history of a problem, such as the Arab-Israeli conflict, or go to vote in an election. The question of changing our Constitution to recognize the Aborigines brings questions of Australian history and legal history together. Whether we support gay marriage may and should be affected by our understanding of the role of marriage in society in times past as well as today. Our decisions and our beliefs, and those of political leaders can and should be affected by our understanding of history. The forgetting of history is a forgetting of ourselves.

[All quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from Is History fiction? by Ann Curthoys and John Docker, University of New South Wales Press, 2006.]

No comments:

Post a Comment