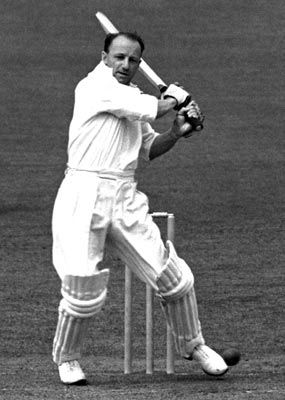

I have a suspicion of revisionist history. All too often it’s someone trying to make a name for themselves by courting controversy rather than revealing genuine new evidence or ideas. For example a few months ago, a writer on The Punch gave us a column taking on the great Australian cricketer Don Bradman, saying that Don had trouble dealing with some of his team mates to the point where they didn’t like him, and he was possibly involved in questionable business deals in Adelaide. The writing suggested the journalist was being bold and iconoclastic. His content however was nothing you wouldn’t have read in any number of standard biographies of the man, even by an admirer. His column was perhaps twenty years too late to be brave or controversial.

I have a suspicion of revisionist history. All too often it’s someone trying to make a name for themselves by courting controversy rather than revealing genuine new evidence or ideas. For example a few months ago, a writer on The Punch gave us a column taking on the great Australian cricketer Don Bradman, saying that Don had trouble dealing with some of his team mates to the point where they didn’t like him, and he was possibly involved in questionable business deals in Adelaide. The writing suggested the journalist was being bold and iconoclastic. His content however was nothing you wouldn’t have read in any number of standard biographies of the man, even by an admirer. His column was perhaps twenty years too late to be brave or controversial.

However, the historical consensus can be wrong. In Australia of course, we have the example of the Aboriginals. When I was as school we learned about Aboriginal culture a bit, but it all just sort of stopped once Arthur Phillip stepped ashore. Nowadays, the relationship between Colonialist and Native from 1788 to today is one of the great themes of Australian history and society, a source of great argument and controversy and rightly so. So revisionist history has its place for certain.

An area that has been revisited with less fanfare is World War One. We all know about World War One, the pointless war directed by inept callous generals, using outdated tactics safe in their command posts while soldiers were slaughtered needlessly in mud and gas. General Douglas Haig, the Supreme Commander, was particularly inept, one of history’s greatest bunglers. We’ve seen ‘Oh What a lovely war’ and ‘Blackadder goes forth’ both of which encapsulate this view beautifully in popular entertainment.

However, this broad view, however popular and entrenched, may well be wrong. On one level, this makes perfect sense. Part of the popular view is how professional and good the German army was, yet they were defeated by the British army. To win the war, once the Germans has taken part of France, all they really had to do was stay there. Yet the inept British generals created and lead an army that drove them back to the point where they sued for peace. Mind you, if they had driven them all the way to Berlin as Haig and American general Jack Pershing wanted to, perhaps we could have prevented World War Two. But that’s history’s hypotheticals, another area all together.

In the last few years, more and more historians are suggesting that WWI was neither pointless nor badly managed. I’ve read a couple of books in this area, the latest being Mud, blood and poppycock: Britain and the Great War, by Gordon Corrigan, an ex-army officer. It’s a well-argued, clearly written book, taking a topical approach to subjects such as the causes of the war, Britain losing a generation of men, life in the trenches, the cowardice and incompetence of the Generals, the small contribution by the US forces, justice in the army, and so on. I could explain some of these but it would be easier for you to read the book. Let one example serve: the lost generation. By use of population statistics, Corrigan shows that the number of men between 18 and 35 in Great Britain lost was not nearly as large as we think it was. You could not even say most of the men of this age were killed. However, the number of deaths in war was unprecedented for the British, if not for their European counterparts. Never before had Britain sent such numbers to fight and the number of deaths were commensurate. Moreover, thanks to the Pals Battalions, where men from the same town or the same industry were allowed to stay together when they enlisted, places could lose all or most of their men in one day or one battle. So while in statistical terms, the myth is wrong, in terms of the psychological effect on Britain, the myth still has value. Corrigan is not a mindless iconoclast but an historian looking at evidence with a fresh eye.

And on a smaller note, Douglas Haig was never the Supreme Commander. Throughout the war, he was subordinate to the French who were the senior members of the Allied forces and his decisions, say to keep fighting on the Somme, were forced upon him by circumstances and military necessity.

And on a smaller note, Douglas Haig was never the Supreme Commander. Throughout the war, he was subordinate to the French who were the senior members of the Allied forces and his decisions, say to keep fighting on the Somme, were forced upon him by circumstances and military necessity.

Not that this makes everything okay. Bad mistakes were made, blunders that should have been seen at the time, not just with hindsight. Perhaps the worst day of the war was the last. Thousands of soldiers on both sides were killed between the time of the Armistice being signed early on the morning of November 11 and the time it came into effect. There were many reasons this happened, sometimes pure ignorance, but all too often the sheer bloody-mindedness of the commanding officers, sending men in to take land they could walk into a few hours later. I hope the spirits of the men who died that day rested heavily on the consciences of the men who sent them in.