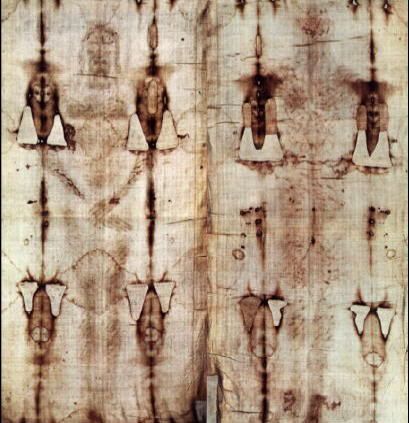

Many years ago, I read a book by an American scientist, an atheist, who was one of an international team of scientists who were given unprecedented access to the Shroud of Turin by the Catholic Church for means of examination and scientific testing. The one test they were not permitted was carbon-dating, as this process destroys what you are testing.

Many years ago, I read a book by an American scientist, an atheist, who was one of an international team of scientists who were given unprecedented access to the Shroud of Turin by the Catholic Church for means of examination and scientific testing. The one test they were not permitted was carbon-dating, as this process destroys what you are testing.

The conclusions of the team were that the figure on the Shroud was formed by blood, contained pollen and dirt consistent with a Middle-Eastern origin, and showed a man who had been whipped with first-century Roman whips, and then crucified and had wounds on his his head consistent with sharp thorns. In short, as far as could be tested, everything showed it to be what it claimed to be: the burial shroud of a man from the Middle East crucified in the first century in same way as Jesus. Beyond that, they could not say more.

The Shroud of Turin, whatever else it is, is a mysterious object. If fake, then how was it done? If real, many more questions arise. But no-one had heard of it until the Middle Ages, and modern carbon testing has declared it a Medieval fake. So much for that.

Ian Wilson is an historian who has been examining the Shroud and historical evidence of the Bible for some time, with many books and television documentaries to his name. In his 2010 book, The Shroud: The 2000-year-old mystery solved he claims to have solved both the major objections to the authenticity of the Shroud. It is, to say the least, a bold claim.

He only spends one chapter on the Carbon Testing, which seems a little slight, but then he can only raise two objections. One, that mistakes happen and other carbon tests have been subsequently found to be way out. But this leads to his more interesting objections: these mistakes have often been due to contamination of the material being tested. The Shroud has been burned, soaked in water, repaired, displayed in front of burning candles and is anything from 700 to 2000 years old, most of that time not nearly as protected as it has been recently. Mmmmmm. Moreover, the strips that were cut for testing were taken from the upper-left corner. For many years, when the Shroud was displayed much more often than it is today, it was held up by clerics, with one at each corner, and on or two in the middle. This corner therefore was one of the most contaminated areas of the Shroud, filled with generations of dirt and sweat and skin cells. It was the area most likely to return a false result. Which then raises the question, why choose it?Short of letting another part of the Shroud being destroyed for more testing, speculation is all that is left for those who want to believe.

He only spends one chapter on the Carbon Testing, which seems a little slight, but then he can only raise two objections. One, that mistakes happen and other carbon tests have been subsequently found to be way out. But this leads to his more interesting objections: these mistakes have often been due to contamination of the material being tested. The Shroud has been burned, soaked in water, repaired, displayed in front of burning candles and is anything from 700 to 2000 years old, most of that time not nearly as protected as it has been recently. Mmmmmm. Moreover, the strips that were cut for testing were taken from the upper-left corner. For many years, when the Shroud was displayed much more often than it is today, it was held up by clerics, with one at each corner, and on or two in the middle. This corner therefore was one of the most contaminated areas of the Shroud, filled with generations of dirt and sweat and skin cells. It was the area most likely to return a false result. Which then raises the question, why choose it?Short of letting another part of the Shroud being destroyed for more testing, speculation is all that is left for those who want to believe.

But as I say, this is only one chapter. Wilson spends most of the book on the other main objection: if it is real, then where was it for the first 1400 years of its existence? His answer for this is to link the Shroud to another mysterious image of Jesus on cloth that disappeared some decades before the Shroud appeared,the Image of Edessa.

Yes, I'd not heard of it either. But accounts of it date back to the 1st century to the town of Edessa, now called Sanliurfa, in modern Turkey, where it was kept from around 30AD to 944AD. Its history, and journey thereafter, are quite complicated, and rather than summarise, I would direct you to the book.

But unlike the objections to the Carbon Dating, this is far more convincing and thorough, even to the point of tediousness. There is much speculation and supposition, as you would expect on any object from the 1st century, but Wilson makes as good a case as he can be done. It would be more convincing, but for the carbon testing.

|

| Leonardo action figure: coming soon! |